News round-up, May 17, 2023

Quote of the day…

“We have a huge responsibility, supplying the rest of Europe with energy,” Defense Minister Bjørn Arild Gram told POLITICO. “To be a stable, reliable producer of energy, of gas, is an important role for us and we take that very seriously. That is why we are also doing so much to protect this infrastructure.”

Scouring the seas for Putin's pipeline saboteurs, POLITICO EU.Most read…

Row over Russian energy sanctions gatecrashes EU-India summit

As Brussels trumpets new trade ties with the South Asian country, officials are split on whether to target energy embargo loopholes.

POLITICO E.U. BY GABRIEL GAVIN AND BARBARA MOENS, MAY 16, 2023 What Happens If a Debt Ceiling Agreement Isn't Reached

Joe Biden and Kevin McCarthy Expected to Resume Debt Limit Talks on Tuesday

TIME BY SOLCYRE BURGA, MAY 15, 2023UBS flags $17 billion hit from Credit Suisse takeover

According to UBS, the assets and liabilities of the combined group will have a negative impact of $13 billion as a result of fair value adjustments. Additionally, it anticipates $4 billion in future legal and regulatory expenses as a result of outflows.

REUTERS By John Revill and Selena LiEU balks at adding Russian gas pipeline ban to sanctions package

The idea isn’t gaining much traction in Brussels, but Kyiv is pushing hard for sanctions to cover gas pipelines.

POLITICO EU BY GABRIEL GAVIN AND VICTOR JACK, MAY 16, 2023 Scouring the seas for Putin's pipeline saboteurs

At sea, on the hunt for Russia's pipeline saboteurs.

POLITICO E.U. by CHARLIE COOPER IN BERGEN, NORWAY. PHOTOS BY INGERD JORDAL FOR POLITICO EU/EDITING BY GERMÁN & CO, MAY 16, 2023Japan embraces G7's gas support but companies may face long-term problems

To achieve its net-zero carbon emission targets and ensure energy security, Japan, the world's largest LNG consumer, is committed to using gas as a transition fuel. However, this commitment contrasts with the demands of the other G7 nations to immediately reduce all fossil fuel consumption.

REUTERS By Katya Golubkova, Yuka Obayashi and Kate AbnettAndrés Gluski, CEO of energy and utility AES CorpHow can strategic investment achieve both economic growth and social progress?… What is the role of renewable energy and battery storage in achieving the goals of the low-carbon economy?…

The AES Corporation President Andrés Gluski, Dominican Republic Minister of Industry and Commerce Victor Bisonó, and Rolando González-Bunster, CEO of InterEnergy Group, spoke at the Latin American Cities Conferences panel on "Facilitating Sustainable Investment in Strategic Sectors" on April 12 in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic.

Today's events

〰️

Today's events 〰️

Foreign Secretary Subrahmanyam Jaishankar denies criticism that India is helping Russia circumvent EU sanctions | Erika Santelices/AFP/Editing by Germán & CoRow over Russian energy sanctions gatecrashes EU-India summit

As Brussels trumpets new trade ties with the South Asian country, officials are split on whether to target energy embargo loopholes.

POLITICO E.U. BY GABRIEL GAVIN AND BARBARA MOENS, MAY 16, 2023 BRUSSELS — Talk at an EU-India summit on Tuesday was meant to be about tech and trade. But the first high-level meeting of its kind ended up being overshadowed by an apparent loophole in Western sanctions against Russia that allows countries like India to buy up cheap oil, refine it, and then ship it back to Europe for a hefty profit.

Speaking at a press conference in Brussels, Indian Foreign Secretary Subrahmanyam Jaishankar denied criticism that his country was helping Moscow circumvent sanctions. Saying he did not "see the basis" for such allegations, New Delhi's top diplomat said EU rules mandate that "if Russian crude is substantially transformed, it’s not treated as Russian anymore."

In earlier comments to the Financial Times the EU's foreign policy chief Josep Borrell broke ranks to say that Brussels should move to crack down on third countries refining Russian oil and selling the products on to the bloc. "If diesel or gasoline is entering Europe ... from India and being produced with Russian oil, that is certainly a circumvention of sanctions and member states will have to take measures," he said.

The row intruded on what was supposed to be an upbeat summit as Brussels hosted the first meeting of the newly created EU-India Trade and Tech Council, designed to foster cooperation between two of the world's largest democracies. It comes in a week of hectic summit diplomacy that will culminate in a G7 summit in Japan where Russia sanctions will top the agenda.

Indian Trade Minister Piyush Goyal said the EU-India relationship has the potential to be the "defining partnership of the 21st century." The EU is meanwhile keen to build closer ties with India in the aftermath of Russia’s invasion of Ukraine and has also moved to resume negotiations with India on a stalled free trade deal.

However, data from shipping platform Kpler, seen by POLITICO, shows that the South Asian nation has become one of the biggest winners from energy sanctions imposed by the West on Russia in the wake of the war in Ukraine. No longer competing for supplies with Europe and other major economies, India has saved around $89 per ton of crude, an analysis from one state-controlled bank reports.

As a result, since the start of Moscow's full-scale invasion, Indian imports of Russian crude oil have shot up from around 1 million barrels a month to more than 63 million barrels in April alone.

At the same time, its lucrative exports of refined oil products to the EU have skyrocketed, raising concerns that it is simply selling on processed Russian supplies.

European imports of diesel from India saw an almost tenfold increase last month compared to the same time last year, with member states buying over 5 million barrels, while the flow of jet fuel to the Continent soared by more than 250 percent to a total of 2.49 million barrels.

RUSSIAN OIL EXPORTS TO INDIA HAVE SKYROCKETED ...

Seaborne exports of Russian crude oil to India, in barrels sold per month.

... WHILE INDIA IS SHIPPING MORE FUEL TO THE EU

Seaborne exports of Indian jet fuel and diesel fuel to the EU, in barrels sold per month.

'Legal but immoral'

In February, the EU imposed a ban on Russian refined oil products, building on an embargo on crude imposed last year. However, fuel from Russian oil produced by refineries in third countries has proven harder to crack down on.

“We have enough evidence that some international companies are buying refinery products made from Russian oil and selling them on to Europe,” Oleg Ustenko, an economic adviser to Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelenskyy, told POLITICO in March. “It’s completely legal, but completely immoral. Just because it’s allowed doesn’t mean we don’t need to do anything about it.”

Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has consistently defied pressure to impose sanctions on Russia or scale back close economic ties with the Kremlin. “India is on the side of peace and will remain firmly there,” he insisted last September, arguing that his country was under no obligation to weigh into the conflict.

"India has a growing population and the government has set up a massive development agenda which needs increasing energy supplies," said Purva Jain, a New Delhi-based analyst with the Institute for Energy Economics and Financial Analysis.

"When geopolitical disturbances happen, economic opportunities are created. Ultimately these decisions are being driven by energy security concerns," she added.

The discussion on sanctions is particularly sensitive given the EU is currently negotiating its 11th sanctions package against Russia, which focuses on fighting the circumvention of existing economic restrictions. Brussels is considering also hitting third countries with penalties if they are found to be breaking its rules. Although India is not top of mind in that discussion, it could open the door for future measures against New Delhi.

Speaking alongside Foreign Minister Jaishankar, the EU's Commissioner for Competition Margrethe Vestager sought to downplay Borrell's comments. If there are concerns to be raised, she said, "it will be with an extended hand, not a pointed finger."

Another thorny issue between the two powerhouses is the bloc's proposal to impose a tariff of up to 35 percent on carbon-intensive imports, including cement and steel, which are among New Delhi's main trade offerings.

New Delhi is planning to take the dispute with Brussels to the World Trade Organization to overturn the plans, which it says amount to protectionism, Reuters reported earlier. The two sides have now agreed to discuss the upcoming measure in the Trade and Tech Council, as POLITICO previously reported. "I am sure the intention is not to create a barrier to trade but to find a way forward," said Goyal.

PITTSBURGH, PA - APRIL 29, 2019: Former Vice President Joe Biden points to the crowd outside of his first 2020 presidential campaign stop in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Image by Germán & Co via ShutterstockWhat Happens If a Debt Ceiling Agreement Isn't Reached

Joe Biden and Kevin McCarthy Expected to Resume Debt Limit Talks on Tuesday

TIME BY SOLCYRE BURGA, MAY 15, 2023A politically-divided Congress is at a crossroads over raising the U.S. government’s debt ceiling, as the country is on the brink of defaulting on their loans if an agreement isn’t made soon.

The federal debt ceiling was last increased in December 2021, by $2.5 trillion to $31.4 trillion, which the government maxed out in mid-January. The Treasury Department said it has since taken “extraordinary measures” to avoid falling into default on their debt, though Treasury Secretary Janet Yellen warned that the government could run out of money for its bills as early as June 1.

“Given the current projections, it is imperative that Congress act as soon as possible to increase or suspend the debt limit in a way that provides longer-term certainty that the government will continue to make its payments,” Yellen wrote in a letter to House Speaker Kevin McCarthy on May 1.

Lawmakers have made changes to the debt limit more than 100 times since World War II. This year Republicans have vowed to increase the debt ceiling so long as it’s suggested spending cuts are enacted. President Joe Biden, however, wants to see an increase in the debt ceiling separate from any budgetary changes.

Defaulting would “produce an economic and financial catastrophe,” Yellen said in a statement, remarking that the government would not be able to make Social Security payments or invest in future projects. “Congress must vote to raise or suspend the debt limit. It should do so without conditions. And it should not wait until the last minute.”

What are Republicans negotiating for?

On Wednesday, House Republicans passed a spending bill that would increase the debt ceiling but cap federal spending for a decade. The bill, which narrowly passed the House, would also roll back the Biden administration’s energy tax credit, as well as impose certain work requirements on federal social programs, among other measures.

The bill is not likely to move forward in the Democrat-controlled Senate, where many legislators are unhappy with the suggested concessions. President Biden also said he would veto the bill if it reached his desk.

Republicans, however, see it as a step towards negotiations. “We lifted the debt limit; we’ve sent it to the Senate; we’ve done our job,” said House Speaker McCarthy after the bill passed.

What happens if Congress doesn’t reach an agreement?

If no Congressional action is taken and the government reaches its debt ceiling, it will have to default on its financial obligations, although this has yet to happen in history.. This has The government won’t be able to pay salaries for federal employees, veterans’ benefits, and also won’t be able to fund Social Security, affecting some 66 million Americans, though the future of social security is already under question as projections foresee that the fund’s reserves will run out by 2033.

Social Security recipients could temporarily see their checks arrive with a delay, depending on how long it takes politicians to negotiate the debt ceiling.

A default would also seriously impact the global economy, which relies on the relative stability of the United States. The Committee for a Responsible Federal Budget projects that interest rates would increase and investment into Treasury securities would stop, impacting people’s car loans, credit cards, and more.

Previous debt ceiling negotiations were also stalled under the Obama administration, marking a new standard of polarized political battles when it came to discussing the government’s spending budget. In 2011, House Republicans fought for months to decrease the deficit in exchange for a debt ceiling raise, impacting the country’s credit ranking for the first time ever. Discussions culminated two days before the Treasury said the United States would have exhausted all funds. That delay in voting to raise the debt ceiling affected the stock market and led to higher borrowing rates for the U.S. that cost the country an additional $1.3 billion in 2011, according to the United States Government Accountability Office.

President Biden and top congressional lawmakers are set to meet early next week after talks were canceled Friday.

“We’ve not reached the crunch point yet but there’s real discussion about some changes we all could make,” Biden said on Saturday before boarding Air Force One. “But we’re not there yet.”

Correction, May 15The original version of this story misstated how much the debt ceiling last increased. It increased by $2.5 trillion, not from $2.5 trillion.Image by Germán & CoUBS flags $17 billion hit from Credit Suisse takeover

According to UBS, the assets and liabilities of the combined group will have a negative impact of $13 billion as a result of fair value adjustments. Additionally, it anticipates $4 billion in future legal and regulatory expenses as a result of outflows.

REUTERS By John Revill and Selena LiA logo of Swiss bank UBS is seen in Zurich, Switzerland March 29, 2023. REUTERS/Denis Balibouse

May 16 (Reuters) - UBS Group AG (UBSG.S) expects a financial hit of about $17 billion from the takeover of Credit Suisse Group AG (CSGN.S), the bank said in a regulatory presentation as it prepares to complete the rescue of its struggling Swiss rival.

UBS estimates a negative impact of $13 billion from fair value adjustments of the combined group's assets and liabilities. It also sees $4 billion in potential litigation and regulatory costs stemming from outflows.

UBS, however, also estimated it would book a one-off gain stemming from the so-called "negative goodwill" of $34.8 billion by buying Credit Suisse for a fraction of its book value.

The financial cushion will help absorb potential losses and could result in a boost to the lender's second-quarter profit if UBS closes the transaction next month as planned.

UBS said the estimates were preliminary and the numbers could change materially later on. It also said it might book restructuring provisions after that, but offered no numbers.

"The financial information lacks an estimate of restructuring provisions as these will be booked after the transaction closes," Vontobel analyst Andreas Venditti said in a note.

Analysts at Jefferies have estimated restructuring costs, litigation provisions and the planned winding down of the non-core unit could total $28 billion.

Meanwhile, UBS has implemented a number of restrictions on Credit Suisse while the takeover is underway.

In certain cases, Credit Suisse cannot grant a new credit facility or credit line exceeding 100 million Swiss francs ($113 million) to investment-grade borrowers or more than 50 million francs to non-investment-grade borrowers, a UBS filing showed.

"Credit Suisse obviously found itself in a problem because of lapses in its risk controls and I think just setting these parameters on the ability or standards to lend out is not very unreasonable," said Benjamin Quinlan, Hong Kong-based chief executive of financial consultancy firm Quinlan & Associates

"Ultimately, from UBS' perspective, they will have to wear these risks on their books."

Credit Suisse also cannot undertake capital expenses of more than 10 million francs as part of the restrictions or enter into certain contracts worth more than 3 million francs per year.

The filing shows Credit Suisse cannot order any "material amendments" to its employee terms and conditions, including remuneration and pension entitlements, till deal closure.

The restrictions "will cause certain clients to leave Credit Suisse" but may not accelerate the pace of outflows already seen, said Quinlan, following UBS' statement last week that Credit Suisse had already stemmed asset outflows.

RUSHED INTO DEAL

UBS said it was rushed into the deal and had less than four days to complete due diligence given the 'emergency circumstances' as Credit Suisse's financial health worsened.

UBS agreed in March to buy Credit Suisse for 3 billion Swiss francs ($3.4 billion) in stock and to assume up to 5 billion francs in losses that would stem from winding down part of the business, in a shotgun merger engineered by Swiss authorities over a weekend amid a global banking turmoil.

The deal, the first rescue of a global bank since the 2008 financial crisis, will create a wealth manager with more than $5 trillion in invested assets and over 120,000 employees globally.

The Swiss state is backing the deal with up to 250 billion Swiss francs in public funds.

Switzerland's government is providing a guarantee of up to 9 billion francs for further potential losses on a clearly defined part of Credit Suisse portfolio.

UBS signaled no quick turnaround for the 167-year-old Credit Suisse, which came to the brink of collapse during the recent banking sector turmoil after years of scandals and losses.

It said it expected both the Credit Suisse group and its investment bank to report substantial pre-tax losses in the second quarter and the whole of this year.

Following the legal closing of the transaction, UBS Group AG plans to manage two separate parent companies – UBS AG and Credit Suisse AG, UBS said last week. It has said the integration process could take three to four years.

During that time, each institution will continue to have its own subsidiaries and branches, serve its clients and deal with counterparties.

G7 members like Germany and Italy still have pipeline links to Russia, even if their flow of gas has drastically dropped | John MacDougall/AFP/Editing by Germán & CoEU balks at adding Russian gas pipeline ban to sanctions package

The idea isn’t gaining much traction in Brussels, but Kyiv is pushing hard for sanctions to cover gas pipelines.

POLITICO EU BY GABRIEL GAVIN AND VICTOR JACK, MAY 16, 2023 The EU is unlikely to amend its 11th Russia sanctions package to permanently shut natural gas pipelines the Kremlin turned off following its invasion of Ukraine, even though it's up for discussion at the upcoming G7 summit, diplomats told POLITICO.

According to draft conclusions seen by the Financial Times, the G7 club of rich democracies meeting in Japan is mulling a measure that would bar countries like Germany and Poland from resuming imports of natural gas from Russia even if the Kremlin decides to turn the taps back on.

But that would have to be accepted by G7 members like Germany and Italy, which still have pipeline links to Russia, even if the gas flowing through them has dropped off to almost nothing, and EU officials and analysts say there is no consensus in support of the idea.

“From what I hear, it is very unlikely this will pass,” said one diplomat from an EU country that had its Russian gas cut off last year, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss the sensitive negotiations.

“There is too much resistance from the countries dependent on the remaining gas,” the diplomat added. “The 11th sanctions package is almost done and inserting this huge measure at this moment is not going to work.”

Before the full-scale invasion of Ukraine, Russia supplied over 40 percent of the EU's gas imports. That's now fallen to less than 8 percent, according the Bruegel think tank.

Two of the largest prewar routes, the undersea Nord Stream pipeline to Germany and the Yamal pipeline running across Poland, have seen flows drop to zero. Transit via pipelines running across Ukraine is about a quarter of the prewar level, with only the TurkStream pipeline across the Black Sea running at levels similar to before the invasion.

Russia has dangled the possibility of reopening the taps; President Vladimir Putin in October said his country is ready to restart supplies if necessary.

The G7 gambit is designed to “curb attempts to resurrect Nord Stream,” above all to quell voices in Germany and any other countries where there “may be companies and consumers who may be interested in resuming imports” of Russian pipeline gas one day, said Aura Sabadus, a senior analyst at the market intelligence firm ICIS.

It could also help build pressure for including pipelines in an eventual 12th round of EU sanctions.

That's exactly what Kyiv hopes will happen.

“The prohibition of pipeline imports of Russian gas can be a good symbolic step,” Ukrainian Energy Minister German Galushchenko told POLITICO. “It could disable one comfortable way for Russia to blackmail the EU and corrupt European politicians.”

The European Commission declined to comment on the pipeline sanctions report.

Scouring the seas for Putin's pipeline saboteurs

At sea, on the hunt for Russia's pipeline saboteurs.

POLITICO E.U. by CHARLIE COOPER IN BERGEN, NORWAY. PHOTOS BY INGERD JORDAL FOR POLITICO EU/EDITING BY GERMÁN & CO, MAY 16, 2023It’s an hour before dawn breaks over the North Sea. Aboard the KV Bergen, the officer of the watch is wide awake.

The 93-meter long Norwegian Navy Coast Guard vessel is on patrol, 50 miles out to sea. The sky is dark, the sea darker. But off the starboard bow, bright lights gleam through the rain and mist. Something huge and incongruous is looming out of the water, lit like a Christmas display.

“Troll A,” says Torgeir Standal, 49, the ship’s second in command, who is taking the watch on this bleak March morning.

It’s a gas platform — a big one.

Image: by Germán & Co via ShutterstockWhen it was transported out to this desolate spot nearly 30 years ago, Troll A — stretching 472 meters from its seabed foundations to the tip of its drilling rig — became the tallest structure ever moved by people across the surface of the Earth. Last year, Troll, the gas field it taps into, provided 10 percent of the EU’s total supply of natural gas — heating homes, lighting streets, fueling industry.

“There are many platforms here,” says Standal, standing on the dark bridge of the Bergen, his face illuminated by the glow from the radar and satellite screens on his control panel. “And thousands of miles of pipeline underneath.”

And that’s why the Bergen has come to this spot today.

In September 2022, an explosion on another undersea gas pipeline nearly 600 miles away shook the world. Despite three ongoing investigations, there is still no official answer to the question of who blew up the Nord Stream pipe. But the fact that it could happen at all triggered a Europe-wide alert.

Against a backdrop of growing confrontation with Moscow over its brutal invasion of Ukraine and its willingness to use energy as a weapon, the vulnerability of the undersea pipes and cables that deliver gas, electricity and data to the Continent — the vital arteries of comfortable, modern European life — has been starkly exposed.

In response, Norway, alongside NATO allies, increased naval patrols in the North Sea — an area vital for Europe’s energy security. The presence of the Bergen, day and night, in these unforgiving waters, is part of the effort to remain vigilant. The task of the men and women on board is to keep watch on behalf of Europe — and to stop the next Nord Stream attack before it happens.

The officers of the watch

But what are they looking for?

In recent weeks the Bergen has tracked the movements of a Russian military frigate through the North Sea — something that it has to do “several times every year,” says Kenneth Dyb, 47, the skippsjef, or commander of the ship.

The Russians have a right to sail through these seas out to the Atlantic, and it is very unlikely Moscow would be so brazen as to openly attack a gas platform or a pipeline. But, says Dyb, as his ship steams west to another gas and oil field, Oseberg, “it’s important to show that we are present. That we are watching.”

Recent reports that Russian naval ships — with their trackers turned off — were present near the site of the Nord Stream blasts in the months running up to the incident have reinforced the importance of having extra eyes on the water itself.

Of course, the gas didn’t come for free. Norway has profited hugely from the spike in gas and oil prices that followed Putin’s invasion of Ukraine. The state-owned energy giant Equinor made a record $75 billion profit in 2022. Oslo is sensitive to accusations of war profiteering — and keen to show Europe that it cares about its neighbors’ energy security as much as it cares about their cash.

But the threat to the pipelines could also be more low-key. One of the many theories about the Nord Stream attack is that it was carried out by a small group of divers, operating from an ordinary yacht. In such a scenario, something as seemingly innocent as a ship suddenly going stationary, or following an unaccustomed course through the water, could be suspicious. The Bergen’s crew have the authority to board and inspect vessels that its crew consider a cause for concern.

Russia’s covert presence in these waters has been acknowledged by Norway’s intelligence services in recent weeks. A joint investigation by the public broadcasters in Norway, Sweden, Denmark and Finland uncovered evidence of civilian vessels, such as fishing ships, being used for surveillance activities. This is something that has been “going on forever,” according to Ståle Ulriksen, a researcher at the Royal Norwegian Naval Academy, but it has increased in intensity in recent years.

NORWAY'S GAS NETWORK

The map below shows gas-extraction sites in the North Sea, colored in dark purple. Gas reaches its destination, both in Norway and in othe European countries, via pipelines that are mostly underwater. The longest pipleine is 1,164 kilometers long and goes from the Nyhamna plant to Easington, in the U.K. The one going to Niechorze, in Poland, is 900 km long.

Source:Norwegian Petroleum Directorate“We always look for oddities, anything that is unusual, like new ships in the area that have not been here before,” says Magne Storebø, 26, senior petty officer, as he takes the afternoon watch on the bridge later that day.

The sky is leaden and the horizon lost in cloud. Coffee in hand, Storebø casts his eye over the radar and satellite screens as giant windscreen wipers whip North Sea spray from the floor-to-ceiling windows. There are few ships around, all of them familiar to the crew; service vessels plying back and forth from the gas and oil platforms.

The Nord Stream incident and the new security situation has changed the way Storebø thinks about his work, he says.

He is “more aware of the consequences suspicious vessels could have,” he says. “More awake, you could say.”

Soft-spoken and calm beyond his years, Storebø is philosophical about the potential dangers of his work. He has been in the Navy for four years, in which time war has broken out on the European continent and the threat to his home waters has come into sharp focus.

“If you are going to put a rainy cloud over your head and bury yourself down, I don’t think the Navy or the coastguard is the right place to work in,” he says in conversation with two shipmates later that day. “You need to adjust and to look in a positive direction — and to be ready in case things don’t go that way.”

Energy war round two

As Europe emerges from the first winter of its energy war with Russia, its gas supplies have held up better than almost anyone expected.

But as the Continent braces for next winter, the risk of another Nord Stream-style attack to a key pipeline is taken seriously at the highest levels of leadership.

“Things look OK for gas security now,” said one senior European Commission official, speaking on condition of anonymity to discuss sensitive matters of energy security. “But if Norway has a pipeline that blows up, we are in a different situation.”

EU policymakers see four key risks to gas security going into next winter, the senior official added: exceptionally cold weather; a stronger-than-expected Chinese economic recovery hoovering up global gas supply; Russia cutting off the remaining gas it sends to Europe; and last but not least, an “incident” affecting energy infrastructure.

Such an event might not only threaten supply but could potentially spark panic in the gas market, as seen in 2022, driving up prices and hitting European citizens and industries in the wallet. And nowhere is the potential for harm greater than in the North Sea.

Norway is now Europe’s biggest single supplier of gas. After Russian President Vladimir Putin and the energy giant Gazprom shut off supply via Nord Stream and other pipelines, Norway stepped up its own production in the North Sea, delivering well over 100 billion cubic meters to the EU and the U.K. in 2022. European Commission President Ursula Von der Leyen visited Troll A herself in March this year — the first visit of a Commission president to Norway since 2011 — to personally thank the country’s president, Jonas Gahr Støre, for supplies that “helped us through the winter.”

“We have a huge responsibility, supplying the rest of Europe with energy,” Defense Minister Bjørn Arild Gram told POLITICO. “To be a stable, reliable producer of energy, of gas, is an important role for us and we take that very seriously. That is why we are also doing so much to protect this infrastructure.”

The vast majority of that gas is transported into northwest Europe via a complex network of seabed pipes — more than 5,000 miles of them in Norway’s jurisdiction alone. The North Sea has an average depth of just 95 meters. That’s not much deeper than the Nord Stream pipes at the location they were attacked.

“It actually doesn’t take a particularly sophisticated capability to attack a pipeline in relatively shallow waters,” says Sidharth Kaushal, research fellow at the Royal United Services Institute think tank in the U.K.A small vessel, “some divers and an [explosive] charge” are all it could take, Kaushal says.

The navy chief

After the Nord Stream incident in September, suspicion instantly fell on Russia. Moscow has a record of operating in the so-called gray zone — committing hostile acts short of warfare, often covertly.

To date, the three investigations looking into the incident have yet to confirm that suspicion. But European governments — and their militaries — are not taking any chances.

In the days immediately following the explosions, NATO navy chiefs started calling each other to try to coordinate efforts to protect energy infrastructure, says Rune Andersen, the chief of Norway’s navy, speaking to POLITICO at Haakonsvern naval base, before the KV Bergen’s voyage.

Everyone had the same thought, he says. “If that happens in the North Sea, we will have a problem.”

Andersen joined the Navy as a young man in 1988, in the last days of the Cold War. Now 54, he is used to the Russian threat overshadowing Norway’s and Europe’s security.

“After decades of attempts to integrate or cooperate with Russia, we now have war in Europe. We see that our neighbor is brutal and willing to use military force,” he says grimly. “I worked in the Navy in the ’90s when it was enduring peace and partnership on the agenda. We are back to a situation where our job feels more meaningful — and necessary.”

Kenneth Dyb, the skippsjef, or commander of the shipHowever, he points out, his own forces have so far not seen any Russian movements or operations “that are different to what they were before” the Nord Stream attacks. “The job we are doing is precautionary, rather than tailored to any specific threat,” he adds.

Even so, those early discussions with NATO allies have now formalized into daily coordination via the Allied Maritime Command headquarters in the U.K., to ensure there are always NATO ships on hand that can act as “first responders” to potential incidents. British, German and French ships have joined their Norwegian counterparts in the monitoring and surveillance effort.

It is “by nature challenging” to protect every inch of pipeline, all of the time, Andersen says.

The role of the Bergen and ships like it, he adds, is just “one bit of the puzzle.” Simply by their presence at sea, these ships increase the chances of catching would-be saboteurs in the act, and hopefully deter them from trying in the first place.

The goal, in other words, is to reduce the size of the “gray zone” — or to “increase the resolution” of the navy’s picture of the activity out on the North Sea, as Andersen puts it.

In collaboration with the energy companies and pipeline operators, unmanned underwater vehicles — drones — using cameras and high-resolution sonar have been used, Andersen says, to “map the micro-terrain” around pipelines. These are sensitive enough to spot an explosive charge or other signs of foul play.

Equinor, alongside the pipeline operator Gassco, has carried out a “large inspection survey” of its undersea pipeline infrastructure, a company spokesperson says. The survey revealed “no identified signs of malicious activities” but pipeline inspections are ongoing “continuously.”

Senior Petty Officer Simen Strand speaks to the crew. “We haven’t had much to fear in the past, we are probably less naïve nowadays,” he says.

Perhaps understandably, the heightened level of alert has led to the occasional false alarm. A spate of aerial drone sightings near Norwegian energy infrastructure around the time of the Nord Stream attacks last year included a report of a suspicious craft circling above Haakonsvern naval base itself.

“After a while, we concluded it was a seagull,” says Andersen, with the shadow of a grin.

Europe on alert

The navy chief is nonetheless deadly serious about the potential threat. A Nord Stream-style attack in the North Sea is possible. Anderson will not be drawn on the most vulnerable points in the network, saying only that “easy to access” places and “key hubs” are “two things in the back of mind when we think [about] risk.”

Throughout Europe, the alert has been raised. This month, NATO warned of a “significant risk” that Russia could target undersea pipelines or internet cables as part of its confrontation with the West.

Several countries are increasing patrols and underwater surveillance capabilities. The British Royal Navy accelerated the purchase of two specialist ocean surveillance ships, the first of which will be operational this summer. The EU and NATO have established a new joint task force focusing on critical infrastructure protection, and a “coordination cell” has been established at NATO headquarters in Brussels to improve “engagement with industry and bring key military and civilian stakeholders together” to keep the cables and pipelines secure.

Norway — and Europe — are in this struggle for the long haul, Andersen believes.

Indeed, even as Europe transitions from fossil fuels to green energy, the North Sea will remain a vital powerhouse of offshore wind energy, with plans for a huge expansion over the next 25 years. Earlier this year, the Netherlands’ intelligence services reported a Russian ship seeking to map wind farm infrastructure in the Dutch sector of the North Sea. “We think the Russians wanted to investigate the possibilities for potential future sabotage,” Jan Swillens, head of the Dutch Military Intelligence and Security Service tells POLITICO in an emailed statement. “This incident makes clear that these kinds of Russian operations are performed closer than one might think.”

At the same time in the Baltic, countries are shoring up security around their infrastructure, at sea and on land. Late last year, Estonia carried out an underwater inspection of the two Estlink power cables and the Baltic Connector gas pipeline linking it to Finland, the Estonian navy says. Lithuania, meanwhile, is paying “special attention” to security around its LNG terminal at Klaipėda and the gas cargoes that arrive there, a defense ministry spokesperson says.

It was in Lithuania that Europe had its first major false alarm since the Nord Stream incident, when a gas pipeline on land exploded on a Friday evening in January. Foul play was briefly considered a possibility in the immediate aftermath but was quickly ruled out. The pipe was 40 years old, and had been subject to a technical fault.

The danger posed by Russia to infrastructure throughout Europe should not be underestimated, says Vilmantas Vitkauskas, director of Lithuania’s National Crisis Management Centre and a former NATO intelligence official.

“We know their way of thinking, [the way] they send signals or apply pressure,” Vitkauskas says. “We understand Russia quite well, and we are quite worried by what we see — and how vulnerable our infrastructure is in Europe.”

The watchers on the water

Back aboard the Bergen, life for the sailors carries on as normal. It’s a young crew, with an average age of around 30. Some are conscripts. It’s still compulsory in Norway for 19-year-olds to present themselves for national service, but only around one in four are actually recruited for the mandated 19-month stint.

The days are long. Surveillance, maintenance and exercises in search and rescue are all part of the crew’s regular routine. A helicopter from one of the Oseberg oil and gas platforms soars overhead, and the crew are drafted into an exercise winching people on and off the deck of the Bergen in the dead of night, simulating a rescue operation.

The ship needs to be ready to respond to an incident should the call come in from naval headquarters that help is required, or a suspicious vessel has been identified in their patch of the North Sea. But in their downtime, the sailors head to the gym on the lower deck, or play FIFA on the X-box in the sparse games room. Three hearty meals a day are served in the galley kitchen. There is even a ship’s band, cheekily named “Dyb Purple” after their commander. Dyb “takes it well,” says Senior Petty Officer Storebø.

In the daily whirl of activity, most of the young sailors don’t think of their work in the grand strategic sense of protecting the energy security — the warmth, the light, the industry — of an entire continent.

But the context of the Ukraine war — and the precedent set by the Nord Stream attack — has added a note of solemnity just below the surface of the comradeship and bonhomie.

“We are probably less naïve nowadays,” says 33-year-old Senior Petty Officer Simen Strand, who has a wife and two children, a boy and a girl, back home in Bergen. “We haven’t had much to fear in the past, there hasn’t been a concrete threat.”

Storebø agrees but is characteristically sanguine. “Russia has always been there … I’ve not personally felt any more unease than before.”

The next day, Storebø has the night watch, from midnight to four in the morning, as the Bergen travels back to base for a short stop before heading out to sea again.

It’s dark up on the bridge, with the glow of the control panel screens the only light inside. Twenty miles away, little lights can be seen on the Norwegian coast. A lighthouse flares to the south, at Slåtterøy, not far from Storebø’s home island of Austevoll. Beneath the waves, unseen, gas flows from the Troll field back to the mainland, where it is processed. From there, it continues its journey south to light the dark of European nights.

All is quiet but Storebø can’t afford to lose focus. “Coffee and music help,” he says. “I like the night shifts.”

As the officer of the watch, he has to be ready, should the radar, the satellites, or his own eyes see something out of the ordinary — ready to call the captain and raise the alarm.

That’s the job, he says. “You always have it in the back of your mind.”

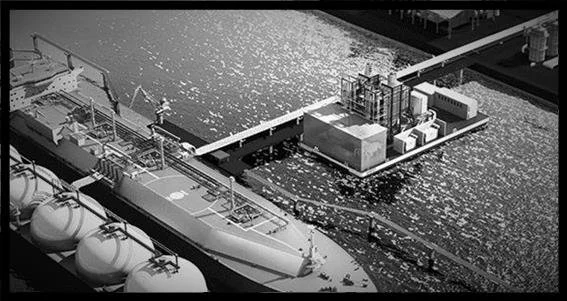

Seaboard: pioneers in power generation in the country

…Armando Rodríguez, vice-president and executive director of the company, talks to us about their projects in the DR, where they have been operating for 32 years.

More than 32 years ago, back in January 1990, Seaboard began operations as the first independent power producer (IPP) in the Dominican Republic. They became pioneers in the electricity market by way of the commercial operations of Estrella del Norte, a 40MW floating power generation plant and the first of three built for Seaboard by Wärtsilä.

Image: Germán & CoCooperate with objective and ethical thinking…

A liquefied natural gas (LNG) tanker is tugged towards a thermal power station in Futtsu, east of Tokyo, Japan November 13, 2017. REUTERS/Issei Kato/File Photo/Editing by Germán & CoJapan embraces G7's gas support but companies may face long-term problems

To achieve its net-zero carbon emission targets and ensure energy security, Japan, the world's largest LNG consumer, is committed to using gas as a transition fuel. However, this commitment contrasts with the demands of the other G7 nations to immediately reduce all fossil fuel consumption.

REUTERS By Katya Golubkova, Yuka Obayashi and Kate AbnettTOKYO, May 17 (Reuters) - Japan's energy companies were quick to embrace the G7's support for natural gas investment in their statement last month but analysts caution that relying on the fossil fuel may open the companies up to long-term problems.

Resource poor Japan, the world's biggest buyer of liquefied natural gas (LNG), is committed to gas as a transition fuel to reach its net-zero carbon emission goals while ensuring energy security but that conflicts with the demands from other G7 members to curb all fossil fuel use sooner rather than later.

a new report said on Tuesday.00:1001:54

Japan's insistence on continuing to rely on gas may delay reaching global climate change goals, especially as its energy companies reap large profits from their investments in the sector, climate activists say.

The meeting of G7 climate ministers eventually agreed last month, despite tussles between Japan and European nations, that gas investments "can be appropriate to help address potential market shortfalls" as a result of Russia's invasion of Ukraine and the disruptions it has caused to global energy markets.

On Monday, Takehiro Honjo, the chairman of the Japan Gas Association, said the fact the G7 made it clear that it is appropriate to invest in natural gas mitigates some of investment risk for Japanese companies looking to continue their spending on projects.

But analysts warn that in the long-term Japan's goals to cut out carbon emissions from its energy sector will reduce the value of future gas projects.

"The short lead time of shale gas or LNG export projects as well as the contract flexibility fit well with what major consumers including Japan and Europe are looking for in the era of uncertainty," said Yoko Nobuoka, senior analyst of Japan power research at Refinitiv.

"But I think Japanese companies will generally hesitate to be involved in gas projects in the future, especially those with long lead times. The main reason is the country's long-term decarbonization ambition," she said.

Japan's support for gas clashes with findings that new investments in gas, which is mainly composed of the greenhouse gas methane and produces CO2 emissions when burned for energy, would undermine climate goals.

The International Energy Agency (IEA) has said no new investments in fossil fuel supply can be made if the world is to limit global warming to 1.5 degrees Celsius (2.7 Fahrenheit).

But, gas investments have been lucrative for Japan's energy companies resulting in record profits.

Other G7 nations, including Germany, have also spent money on LNG infrastructure after the Ukraine invasion.

Japan's is also acutely dependent on gas from Russia, the country's third-largest supplier, especially from the Sakhalin Island LNG project.

"IMPORTANT RESOURCE"

Because of that dependency, Japanese energy companies are keen to diversify their gas supply sources to include Australia and the U.S.

Trading house Marubeni Corp (8002.T) believes gas "will be utilised as a very important resource in the future", Chief Executive Officer Masumi Kakinoki said last week.

Tokyo Gas (9531.T), the Japanese capital's main gas supplier with assets in LNG and other fossil fuels, also hailed the G7 language on gas as it plans to keep investing in gas infrastructure in Asia and U.S. shale gas upstream assets.

Japan's biggest oil refiner Eneos Holdings (5020.T) plans to invest 180 billion yen over the three years in its oil and gas upstream segment, including for the additional development of LNG in Asia.

But, Japan's stated intention to lower its carbon emissions may mean these gas investments carry some risk.

The G7 climate and energy ministers also set big new collective targets for solar power and offshore wind capacity, agreeing to speed up renewable energy, which may eat into gas demand.

The IEA sees global gas consumption reaching a plateau this decade and data from Japan's finance ministry shows that demand in the country is on a downwards trajectory over the past few months.

Gas assets, both upstream and LNG, could start to be seen as stranded already in around 2030, Refinitiv's Nobuoka said.

"New investments in gas not only risk being stranded but will also likely fail to deliver the needed transition", said Maria Pastukhova, senior policy advisor at independent climate think tank E3G.

"There are ample clean energy solutions that can deliver energy access and security faster and in a more sustainable way."