News round-up, May 22, 2023

Has the energy sector enough coverage?

“It's imperative to maintain a broader perspective when it comes to the energy sector. Although there may be adequate coverage, we must be mindful of our natural inclination towards self-centeredness and disregard for the bigger picture. Constructing an objective viewpoint for ourselves and those around us is essential, and maintaining a global outlook is crucial.

Most Read…

The U.S. Needs Minerals for Electric Cars. Everyone Else Wants Them Too.

The United States is entering an array of agreements to secure the critical minerals necessary for the energy transition, but it’s not clear which of the arrangements can succeed.

NYT By Ana Swanson, Reporting from Washington, May 21, 2023Rice Gets Reimagined, From the Mississippi to the Mekong

The challenges rice farmers face in global warming are dire. The survival of billions hinges on successful rice harvests, making it imperative that we address the difficulties of climate change. The unpredictable weather patterns, ranging from droughts to floods, coupled with the salinity of the sea, are detrimental to the crop's growth. Plus, warmer nights contribute to diminishing yields. It is time we take action and aid our rice farmers in overcoming these obstacles.

NYT By Somini Sengupta, reporting from Arkansas and Bangladesh, and Tran Le Thuy, from Vietnam. Thanh Nguyen photographed in Vietnam and Rory Doyle in Arkansas, May 22 05 23.EU hits Meta with record €1.2B privacy fine

Tech giant transferred Europeans’ data to the US unlawfully, Irish privacy regulator said.

POLITICO EU BY CLOTHILDE GOUJARD AND MARK SCOTT, MAY 22, 2023Column: Spot LNG price drops to level that's not too hot, not too cold

The cost of LNG shipped to North Asia fell to $9.80 per million British thermal units (mmBtu) in the week ending May 19, marking its first dip beneath the $10 threshold in two years.

REUTERS By Clyde Russell/Editing by Germán & CoEU Parliament delays renewable energy vote after late backlash

The EU needs help to pass a law requiring 42.5% of its energy from renewables by 2030. Some countries, including France, have yet to support the proposal.

REUTERS By Kate Abnett/EDITING BY GERMÁN & COThe AES Corporation President Andrés Gluski, Dominican Republic Minister of Industry and Commerce Victor Bisonó, and Rolando González-Bunster, CEO of InterEnergy Group, spoke at the Latin American Cities Conferences panel on "Facilitating Sustainable Investment in Strategic Sectors" on April 12 in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic.How can strategic investment achieve both economic growth and social progress?… What is the role of renewable energy and battery storage in achieving the goals of the low-carbon economy?…

The Chaerhan Salt Lake in Golmud, China, where brine is processed to extract lithium and other minerals.Credit...Qilai Shen for The New York Times/Editing by Germán & CoThe U.S. Needs Minerals for Electric Cars. Everyone Else Wants Them Too.

The United States is entering an array of agreements to secure the critical minerals necessary for the energy transition, but it’s not clear which of the arrangements can succeed.

NYT By Ana Swanson, Reporting from Washington, May 21, 2023For decades, a group of the world’s biggest oil producers has held huge sway over the American economy and the popularity of U.S. presidents through its control of the global oil supply, with decisions by the Organization of the Petroleum Exporting Countries determining what U.S. consumers pay at the pump.

As the world shifts to cleaner sources of energy, control over the materials needed to power that transition is still up for grabs.

China currently dominates global processing of the critical minerals that are now in high demand to make batteries for electric vehicles and renewable energy storage. In an attempt to gain more power over that supply chain, U.S. officials have begun negotiating a series of agreements with other countries to expand America’s access to important minerals like lithium, cobalt, nickel and graphite.

But it remains unclear which of these partnerships will succeed, or if they will be able to generate anything close to the supply of minerals the United States is projected to need for a wide array of products, including electric cars and batteries for storing solar power.

Leaders of Japan, Europe and other advanced nations, who are meeting in Hiroshima, agree that the world’s reliance on China for more than 80 percent of processing of minerals leaves their nations vulnerable to political pressure from Beijing, which has a history of weaponizing supply chains in times of conflict.

On Saturday, the leaders of the Group of 7 countries reaffirmed the need to manage the risks caused by vulnerable mineral supply chains and build more resilient sources. The United States and Australia announced a partnership to share information and coordinate standards and investment to create more responsible and sustainable supply chains.

“This is a huge step, from our perspective — a huge step forward in our fight against the climate crisis,” President Biden said Saturday as he signed the agreement with Australia.

But figuring out how to access all of the minerals the United States will need will still be a challenge. Many mineral-rich nations have poor environmental and labor standards. And although speeches at the G7 emphasized alliances and partnerships, rich countries are still essentially competing for scarce resources.

Japan has signed a critical minerals deal with the United States, and Europe is in the midst of negotiating one. But like the United States, those regions have substantially greater demand for critical minerals to feed their own factories than supply to spare.

Kirsten Hillman, Canada’s ambassador to the United States, said in an interview that the allied countries had an important partnership in the industry, but that they were also, to some extent, commercial competitors. “It is a partnership, but it’s a partnership with certain levels of tension,” she said.

“It’s a complicated economic geopolitical moment,” Ms. Hillman added. “And we are all committed to getting to the same place and we’re going to work together to do it, but we’re going to work together to do it in a way that’s also good for our businesses.”

“We have to create a market for the products that are produced and created in a way that is consistent with our values,” she said.

The State Department has been pushing forward with a “minerals security partnership,” with 13 governments trying to promote public and private investment in their critical mineral supply chains. And European officials have been advocating a “buyers’ club” for critical minerals with the G7 countries, which could establish certain common labor and environmental standards for suppliers.

Indonesia, which is the world’s biggest nickel producer, has floated the idea of joining with other resource-rich countries to make an OPEC-style producers cartel, an arrangement that would try to shift the power to mineral suppliers.

Indonesia has also approached the United States in recent months seeking a deal similar to that of Japan and the European Union. Biden administration officials are weighing whether to give Indonesia some kind of preferential access, either through an independent deal or as part of a trade framework the United States is negotiating in the Indo-Pacific.

But some U.S. officials have warned that Indonesia’s lagging environmental and labor standards could allow materials into the United States that undercut the country’s nascent mines, as well as its values. Such a deal is also likely to trigger stiff opposition in Congress, where some lawmakers criticized the Biden administration’s deal with Japan.

Jake Sullivan, the national security adviser, hinted at these trade-offs in a speech last month, saying that carrying out negotiations with critical mineral-producing states would be necessary, but would raise “hard questions” about labor practices in those countries and America’s broader environmental goals.

Whether America’s new agreements would take the shape of a critical minerals club, a fuller negotiation or something else was unclear, Mr. Sullivan said: “We are now in the thick of trying to figure that out.”

Cullen Hendrix, a senior fellow at the Peterson Institute for International Economics, said the Biden administration’s strategy to build more secure international supply chains for minerals outside of China had so far been “a bit incoherent and not necessarily sufficient to achieve that goal.”

The demand for minerals in the United States has been spurred in large part by President Biden’s climate law, which provided tax incentives for investments in the electric vehicle supply chain, particularly in the final assembly of batteries. But Mr. Hendrix said the law appeared to be having more limited success in rapidly increasing the number of domestic mines that would supply those new factories.

“The United States is not going to be able to go this alone,” he said.

Biden officials agree that obtaining a secure supply of the minerals needed to power electric vehicle batteries is one of their most pressing challenges. U.S. officials say that the global supply of lithium alone needs to increase by 42 times by 2050 to meet the rising demand for electric vehicles.

Ford’s electric pickup truck on the production line of the company’s plant in Dearborn, Mich.Credit...Brittany Greeson for The New York Times

While innovations in batteries could reduce the need for certain minerals, for now, the world is facing dramatic long-term shortages by any estimate. And many officials say Europe’s reliance on Russian energy following the invasion of Ukraine has helped to illustrate the danger of foreign dependencies.

The global demand for these materials is triggering a wave of resource nationalism that could intensify. Outside of the United States, the European Union, Canada and other governments have also introduced subsidy programs to better compete for new mines and battery factories.

Indonesia has progressively stepped up restrictions on exporting raw nickel ore, requiring it to first be processed in the country. Chile, a major producer of lithium, nationalized its lithium industry in a bid to better control how the resources are developed and deployed, as have Bolivia and Mexico.

And Chinese companies are still investing heavily in acquiring mines and refinery capacity globally.

For now, the Biden administration has appeared wary of cutting deals with countries with more mixed labor and environmental records. Officials are exploring changes needed to develop U.S. capacity, like faster permitting processes for mines, as well as closer partnerships with mineral-rich allies, like Canada, Australia and Chile.

On Saturday, the White House said it planned to ask Congress to add Australia to a list of countries where the Pentagon can fund critical mineral projects, criteria that currently only applies to Canada.

Todd Malan, the chief external affairs officer at Talon Metals, which has proposed a nickel mine in Minnesota to supply Tesla’s North American production, said that adding a top ally like Australia, which has high standards of production regarding environment, labor rights and Indigenous participation, to that list was a “smart move.”

But Mr. Malan said that expanding the list of countries that would be eligible for benefits under the administration’s new climate law beyond countries with similar labor and environmental standards could undermine efforts to develop a stronger supply chain in the United States.

“If you start opening the door to Indonesia and the Philippines or elsewhere where you don’t have the common standards, we would view that as outside the spirit of what Congress was trying to do in incentivizing a domestic and friends supply chain for batteries,” he said.

However, some U.S. officials argue that the supply of critical minerals in wealthy countries with high labor and environmental standards will be insufficient to meet demand, and that failing to strike new agreements with resource-rich countries in Africa and Asia could leave the United States highly vulnerable.

While the Biden administration is looking to streamline the permitting process in the United States for new mines, getting approval for such projects can still take years, if not decades. Auto companies, which are major U.S. employers, have also been warning of projected shortfalls in battery materials and arguing for arrangements that would give them more flexibility and lower prices.

The G7 nations, together with the countries with which the United States has free trade agreements, produce 30 percent of the world’s lithium chemicals and about 20 percent of its refined cobalt and nickel, but only 1 percent of its natural flake graphite, according to estimates by Adam Megginson, a price analyst at Benchmark Mineral Intelligence.

Jennifer Harris, a former Biden White House official who worked on critical mineral strategy, argued that the country should move more quickly to develop and permit domestic mines, but that the United States also needs a new framework for multinational negotiations that include countries that are major mineral exporters.

The government could also set up a program to stockpile minerals like lithium when prices swing low, which would give miners more assurance they will find destinations for their products, she said.

“There’s so much that needs doing that this is very much a ‘both/and’ world,” she said. “The challenge is that we need to responsibly pull up a whole lot more rocks out of the ground yesterday.”

Image: Germán & CoCooperate with objective and ethical thinking…

Rice Gets Reimagined, From the Mississippi to the Mekong

The challenges rice farmers face in global warming are dire. The survival of billions hinges on successful rice harvests, making it imperative that we address the difficulties of climate change. The unpredictable weather patterns, ranging from droughts to floods, coupled with the salinity of the sea, are detrimental to the crop's growth. Plus, warmer nights contribute to diminishing yields. It is time we take action and aid our rice farmers in overcoming these obstacles.

NYT By Somini Sengupta, reporting from Arkansas and Bangladesh, and Tran Le Thuy, from Vietnam. Thanh Nguyen photographed in Vietnam and Rory Doyle in Arkansas, May 22 05 23.Rice is in trouble as the Earth heats up, threatening the food and livelihood of billions of people. Sometimes there’s not enough rain when seedlings need water, or too much when the plants need to keep their heads above water. As the sea intrudes, salt ruins the crop. As nights warm, yields go down.

These hazards are forcing the world to find new ways to grow one of its most important crops. Rice farmers are shifting their planting calendars. Plant breeders are working on seeds to withstand high temperatures or salty soils. Hardy heirloom varieties are being resurrected.

And where water is running low, as it is in so many parts of the world, farmers are letting their fields dry out on purpose, a strategy that also reduces methane, a potent greenhouse gas that rises from paddy fields.

The climate crisis is particularly distressing for small farmers with little land, which is the case for hundreds of millions of farmers in Asia. “They have to adapt,” said Pham Tan Dao, the irrigation chief for Soc Trang, a coastal province in Vietnam, one of the biggest rice-producing countries in the world. “Otherwise they can’t live.”

In China, a study found that extreme rainfall had reduced rice yields over the past 20 years. India limited rice exports out of concern for having enough to feed its own people. In Pakistan, heat and floods destroyed harvests, while in California, a long drought led many farmers to fallow their fields.

Worldwide, rice production is projected to shrink this year, largely because of extreme weather.

Today, Vietnam is preparing to take nearly 250,000 acres of land in the Mekong Delta, its rice bowl, out of production. Climate change is partly to blame, but also dams upstream on the Mekong River that choke the flow of freshwater. Some years, when the rains are paltry, rice farmers don’t even plant a third rice crop, as they had before, or they switch to shrimp, which is costly and can degrade the land further.

The challenges now are different from those 50 years ago. Then, the world needed to produce much more rice to stave off famine. High-yielding hybrid seeds, grown with chemical fertilizers, helped. In the Mekong Delta, farmers went on to produce as many as three harvests a year, feeding millions at home and abroad.

Today, that very system of intensive production has created new problems worldwide. It has depleted aquifers, driven up fertilizer use, reduced the diversity of rice breeds that are planted, and polluted the air with the smoke of burning rice stubble. On top of that, there’s climate change: It has upended the rhythm of sunshine and rain that rice depends on.

Perhaps most worrying, because rice is eaten every day by some of the world’s poorest, elevated carbon dioxide concentrations in the atmosphere deplete nutrients from each grain.

Rice faces another climate problem. It accounts for an estimated 8 percent of global methane emissions. That’s a fraction of the emissions from coal, oil and gas, which together account for 35 percent of methane emissions. But fossil fuels can be replaced by other energy sources. Rice, not so much. Rice is the staple grain for an estimated three billion people. It is biryani and pho, jollof and jambalaya — a source of tradition, and sustenance.

“We are in a fundamentally different moment,” said Lewis H. Ziska, a professor of environmental health sciences at Columbia University. “It’s a question of producing more with less. How do you do that in a way that’s sustainable? How do you do that in a climate that’s changing?”

A risky balance: Rice, or shrimp?

In 1975, facing famine after war, Vietnam resolved to grow more rice.

It succeeded spectacularly, eventually becoming the world’s third-largest rice exporter after India and Thailand. The green patchwork of the Mekong Delta became its most prized rice region.

At the same time, though, the Mekong River was reshaped by human hands.

Starting in southeastern China, the river meanders through Myanmar, Laos, Thailand and Cambodia, interrupted by many dams. Today, by the time it reaches Vietnam, there is little freshwater left to flush out seawater seeping inland. Rising sea levels bring in more seawater. Irrigation canals turn salty. The problem is only going to get worse as temperatures rise.

“We now accept that fast-rising salty water is normal,” said Mr. Pham, the irrigation chief. “We have to prepare to deal with it.” Where saltwater used to intrude 30 kilometers or so (about 19 miles) during the dry season, he said, it can now reach 70 kilometers inland.

Climate change brings other risks. You can no longer count on the monsoon season to start in May, as before. And so in dry years, farmers now rush to sow rice 10 to 30 days earlier than usual, researchers have found. In coastal areas, many rotate between rice and shrimp, which like a bit of saltwater.

But this requires reining in greed, said Dang Thanh Sang, 60, a lifelong rice farmer in Soc Trang. Shrimp bring in high profits, but also high risks. Disease sets in easily. The land becomes barren. He has seen it happen to other farmers.

So, on his seven acres, Mr. Dang plants rice when there’s freshwater in the canals, and shrimp when seawater seeps in. Rice cleans the water. Shrimp nourishes the soil. “It’s not a lot of money like growing only shrimp,” he said. “But it’s safer.”

Elsewhere, farmers will have to shift their calendars for rice and other staple grains, researchers concluded in a recent paper. Scientists are already trying to help them.

Secrets of ancient rice

The cabinet of wonders in Argelia Lorence’s laboratory is filled with seeds of rice — 310 different kinds of rice.Many are ancient, rarely grown now. But they hold genetic superpowers that Dr. Lorence, a plant biochemist at Arkansas State University, is trying to find, particularly those that enable rice plants to survive hot nights, one of the most acute hazards of climate change. She has found two such genes so far. They can be used to breed new hybrid varieties.

“I am convinced,” she said, “that decades from now, farmers are going to need very different kinds of seeds.”

Dr. Lorence is among an army of rice breeders developing new varieties for a hotter planet. Multinational seed companies are heavily invested. RiceTec, from which most rice growers in the southeastern United States buy seeds, backs Dr. Lorence’s research.

She is focused on divining valuable genetic traits hidden in the many varieties.Critics say hybrid seeds and the chemical fertilizers they need make farmers heavily dependent on the companies’ products, and because they promise high yields, effectively wipe out heirloom varieties that can be more resilient to climate hazards.

The new frontier of rice research involves Crispr, a gene-editing technology that U.S. scientists are using to create a seed that produces virtually no methane. (Genetically modified rice remains controversial, and only a handful of countries allow its cultivation.)

In Bangladesh, researchers have produced new varieties for the climate pressures that farmers are dealing with already. Some can grow when they’re submerged in floodwaters for a few days.

Others can grow in soils that have turned salty. In the future, researchers say, the country will need new rice varieties that can grow with less fertilizer, which is now heavily subsidized by the state. Or that must tolerate even higher salinity levels.

No matter what happens with the climate, said Khandakar M. Iftekharuddaula, chief scientific officer at the Bangladesh Rice Research Institute, Bangladesh will need to produce more. Rice is eaten at every meal. “Rice security is synonymous with food security,” he said.

Less watery rice paddies?

Rice is central to the story of the United States. It enriched the coastal states of the American South, all with the labor of enslaved Africans who brought with them generations of rice-growing knowledge.

Today, the country’s dominant rice-growing area is spread across the hard clay soil near where the Mississippi River meets one of its tributaries, the Arkansas River. It looks nothing like the Mekong Delta. The fields here are laser-leveled flat as pancakes. Work is done by machine. Farms are vast, sometimes more than 20,000 acres.

What they share are the hazards of climate change. Nights are hotter. Rains are erratic. And there’s the problem created by the very success of so much intensive rice farming: Groundwater is running dangerously low.

Enter Benjamin Runkle, an engineering professor from the University of Arkansas at Fayetteville. Instead of keeping rice fields flooded at all times, as growers have always done, Dr. Runkle suggested that Arkansas farmers let the fields dry out a bit, then let in the water again, then repeat. Oh, and would they let him measure the methane coming off their fields?

Mark Isbell, a second-generation rice farmer, signed up.

New irrigation ideas can save water and cut methane emissions.

Dr. Runkle: “A breathalyzer test of the land.”

On the edge of Mr. Isbell’s field, Dr. Runkle erected a tall white contraption that an egret might mistake for a cousin. The device measured the gases produced by bacteria stewing in the flooded fields. “It’s like taking a breathalyzer test of the land,” Dr. Runkle said.

His experiment, carried out over seven years, concluded that by not flooding the fields continuously, farmers can reduce rice methane emissions by more than 60 percent.

Other farmers have taken to planting rice in rows, like corn, and leaving furrows in between for the water to flow. That, too, reduces water use and, according to research in China, where it’s been common for some time, cuts methane emissions.

The most important finding, from Mr. Isbell’s vantage point: It reduces his energy bills to pump water. “There are upsides to it beyond the climate benefits,” he said.

By cutting his methane emissions, Mr. Isbell was also able to pick up some cash by selling “carbon credits,” which is when polluting businesses pay someone else to make emissions cuts.

When neighbors asked him how that went, he told them he could buy them a drink and explain. “But it will have to be one drink,” he said. He made very little money from it.

However, there will be more upsides soon. For farmers who can demonstrate emissions reductions, the Biden administration is offering federal funds for what it calls “climate smart” projects. Agriculture Secretary Tom Vilsack came to Mr. Isbell’s farm last fall to promote the program. Mr. Isbell reckons the incentives will persuade other rice growers to adopt alternate wetting and drying.

“We kind of look over the hill and see what’s coming for the future, and learn now,” said his father, Chris Isbell.

It's the largest fine imposed under the bloc's flagship General Data Protection Regulation | John Edelson/EAFP/Editing by Germán & CoEU hits Meta with record €1.2B privacy fine

Tech giant transferred Europeans’ data to the US unlawfully, Irish privacy regulator said.

POLITICO EU BY CLOTHILDE GOUJARD AND MARK SCOTT, MAY 22, 2023U.S tech giant Meta has been hit with a record €1.2 billion fine for not complying with the EU’s privacy rulebook.

The Irish Data Protection Commission announced on Monday that Meta violated the General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) when it shuttled troves of personal data of European Facebook users to the United States without sufficiently protecting them from Washington's data surveillance practices.

It's the largest fine imposed under the bloc's flagship General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) privacy law and it comes on the eve of the fifth anniversary of the law's enforcement on May 25.

Amazon was previously fined €746 million by Luxembourg and the Irish regulator also imposed four fines against Meta's platforms Facebook, Instagram and WhatsApp ranging between €405 million and €225 million in the past two years.

Ywatchdog said that Meta's use of a legal instrument known as standard contractual clauses (SCCs) to move data to the U.S. "did not address the risks to the fundamental rights and freedoms" of Facebook's European users raised by a landmark ruling from the EU's top court.

The European Court of Justice in 2020 struck down an EU-U.S. data flows agreement known as the Privacy Shield over fears of U.S. intelligence services' surveillance practices. In the same judgment, the top EU court also tightened requirements to use SCCs, another legal tool widely used by companies to transfer personal data to the U.S.

Meta — as well as other international companies — kept relying on the legal instrument as European and U.S. officials struggled to put together a new data flows arrangement and the U.S. tech giant lacked other legal mechanisms to transfer its personal data.

The EU and U.S. are finalizing a new data flow deal that could come as early as July and as late as October. Meta has until October 12 to stop relying on SCCs for their transfers.

The U.S. tech giant previously warned that if it would be forced to stop using SCCs without a proper alternative data flow agreement in place, it could shut down services like Facebook and Instagram in Europe.

Meta also has until November 12 to delete or move back to the EU the personal data of European Facebook users transferred and stored in the U.S. since 2020 and until a new EU-U.S. deal is reached.

“This decision is flawed, unjustified and sets a dangerous precedent for the countless other companies transferring data between the EU and U.S.," Meta's President of Global Affairs Nick Clegg and Chief Legal Officer Jennifer Newstead said in a statement on Monday.

Clegg and Newstead said the company will appeal the decision and seek a stay with the courts to pause the implementation deadlines. "There is no immediate disruption to Facebook because the decision includes implementation periods that run until later this year," they added.

Max Schrems, the privacy activist behind the original 2013 complaint supporting the case, said: "We are happy to see this decision after ten years of litigation ... Unless U.S. surveillance laws get fixed, Meta will have to fundamentally restructure its systems."

The Irish Data Protection Commission said it disagreed with the fine and measure that it was imposing on Meta but had been forced by the pan-European network of national regulators, the European Data Protection Board (EDPB), after Dublin's initial decision was challenged by four of its peer regulators in Europe.

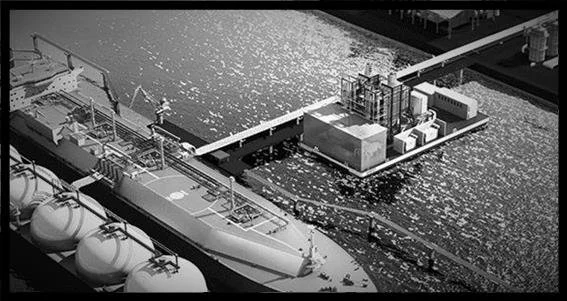

Seaboard: pioneers in power generation in the country…

…“More than 32 years ago, back in January 1990, Seaboard began operations as the first independent power producer (IPP) in the Dominican Republic. They became pioneers in the electricity market by way of the commercial operations of Estrella del Norte, a 40MW floating power generation plant and the first of three built for Seaboard by Wärtsilä.

A liquified natural gas (LNG) tanker leaves the dock after discharge at PetroChina's receiving terminal in Dalian, Liaoning province, China July 16, 2018. REUTERS/Chen Aizhu/File Photo/Editing by Germán & CoColumn: Spot LNG price drops to level that's not too hot, not too cold

The cost of LNG shipped to North Asia fell to $9.80 per million British thermal units (mmBtu) in the week ending May 19, marking its first dip beneath the $10 threshold in two years.

REUTERS By Clyde Russell/Editing by Germán & CoLAUNCESTON, Australia, May 22 (Reuters) - The spot price of liquefied natural gas (LNG) in Asia is in the sweet spot of being low enough to boost buying interest, but not so low that it sparks a surge in demand.

The price for LNG delivered to north Asia dropped to $9.80 per million British thermal units (mmBtu) in the week to May 19, its first foray below the $10 level in two years.

The price has slid 74% since its northern winter peak of $38 per mmBtu on Dec. 16, and is down 86% from the record high of $70.50, hit in August last year as Europe sucked up all available cargoes amid fears of the total loss of Russian pipeline supplies.

The decline in spot LNG prices has seen demand in key Asian importers hold steady, according to data compiled by commodity analysts Kpler.

Asia is expected to import 20.81 million tonnes of the super-chilled fuel in May, the same result as was recorded in April and down slightly from March's 22.16 million.

While a steady-as-she-goes outcome may seem somewhat disappointing at first glance, especially given the price decline, it's actually stronger than appearances given that LNG is in the shoulder period of seasonally weaker demand between the peaks of the northern winter and summer.

The seasonal softness can be seen in Japan's May imports dropping to an expected 4.24 million tonnes from 5.0 million in April and 5.55 million in March.

Japan reclaimed the title of the world's biggest LNG importer from China last year, as Chinese utilities largely opted out of the spot market when prices surged following Russia's invasion of Ukraine.

Chinese buyers have returned to the market, but their purchases have been modest so far in 2023, with an estimated 5.23 million tonnes slated to arrive in May, little changed from April's 5.33 million and 5.46 million in March.

It's believed that Chinese utilities require a spot price below $10 per mmBtu in order for LNG to be competitive in the domestic market, so the decline below this level last week may act to spur some new buying interest in coming weeks.

The price-sensitive LNG buyers in South Asia have also been returning to the spot market in recent months, with India, the fourth-largest importer in Asia, expected to land 1.91 million tonnes in May.

This is slightly down from 1.98 million in April, but up from March's 1.84 million and also well above the 1.46 million in January and the 1.32 million in December, when spot prices were still elevated.

However, it's likely that the decline in spot prices will only boost demand from June onwards, and there are some early signs that this is already happening.

LNG imports by Asia, Europe vs spot price:JUNE PICK-UP

Preliminary June imports for Asia are assessed by Kpler at 19.36 million tonnes, almost matching the May figure, which is a robust signal given the certainty that more cargoes will be assessed in coming weeks.

The lower spot price in Asia is also working to boost buying interest in Europe, with May imports expected at 12.28 million tonnes, up a smidgeon from April's 12.27 million.

Spot LNG prices in Asia are at competitive levels with the main benchmarks in Europe, with the benchmark British day-ahead contract ending at 66.75 pence per therm on May 19, equivalent to $8.18 per mmBtu.

The Dutch TTF front-month contract ended last week at 30.30 euros per megawatt hour, equivalent to about $9.62 mmBtu.

The question for the market is at what point the spot price for LNG in Asia falls far enough to provide a significant boost to buying, especially given the summer demand peak is coming.

The forward curve for LNG futures traded in New York suggests that point is soon, with the curve in contango and the July contract ending at $10.35 per mmBtu on May 19, while August was higher still at $11.11.

The opinions expressed here are those of the author, a columnist for Reuters

European Union flags fly outside the European Commission headquarters in Brussels, Belgium, March 1, 2023.REUTERS/Johanna GeronEU Parliament delays renewable energy vote after late backlash

The EU needs help to pass a law requiring 42.5% of its energy from renewables by 2030. Some countries, including France, have yet to support the proposal.

REUTERS By Kate Abnett/EDITING BY GERMÁN & COBRUSSELS, May 22 (Reuters) - The European Parliament has delayed a planned vote to approve new EU renewable energy targets, after France and other countries lodged last-minute opposition to the law last week, according to an internal email seen by Reuters.

The vote in the Parliament's energy committee had been due to take place on Tuesday. The email said the vote was postponed until June, without specifying a date.

The European Union is attempting to finalise a key pillar of its climate agenda - a law containing a binding goal for the EU to get 42.5% of its energy from renewable sources by 2030.

But the bill has run into late resistance. EU country diplomats had been due to signal their approval for the law last week, but the discussion was shelved after France and other countries said they would not support it.

Parliament had been due to hold a first vote on Tuesday, followed by a final vote in July. A delay risks shelving the policy's approval until September, after the EU assembly's summer recess.

The EU Parliament and EU countries' approval of the law was supposed to be a formality, after negotiators from both sides agreed what was supposed to be a final deal earlier this year.

But France was unhappy with the final result. Paris wants more recognition in the law of low-carbon nuclear energy, and says the rules discriminate against hydrogen produced from nuclear power, by not allowing countries to count this low-carbon fuel towards renewable fuel targets for industry.

Other countries, including Bulgaria, Romania, Poland, were also unhappy with the rules, for a range of reasons including that some capitals view the targets as overly ambitious.

A spokesperson for Sweden, which holds the EU's rotating presidency, said talks were underway to resolve the dispute.

But other countries are impatient, after what some diplomats described as a "surprise" hold-up of one of the bloc's main tools to fight climate change.

"The level of frustration is extremely high indeed. France is always asking for more," one EU diplomat said.